Like my content? Sign up to get occasional emails about new blog posts and other content.

Unsubscribe anytime here.Mocking Lower Layers for Better Test Coverage and Confidence

Something almost every Vue.js application is going to do is make HTTP requests to an API of some sort. This could be for authentication, loading data, or something else. Many patterns have emerged to manage HTTP requests, and even more to test them.

This chapter looks at various ways to architecture your HTTP requests, different ways to test them, and discusses the pros and cons of each approach.

The Login Component

The example I will use is the <login> component. It lets the user enter their username and password and attempt to authenticate. We want to think about:

- where should the HTTP request be made from? The component, another module, in a store (like Vuex?)

- how can we test each of these approaches?

There is no one size fits all solution here. I’ll share how I currently like to structure things, but also provide my opinion on other architectures.

Starting Simple

If you application is simple, you probably won’t need something like Vuex or a specific HTTP request module. You can just inline everything in your component:

<template>

<h1 v-if="user">

Hello, {{ user.name }}

</h1>

<form @submit.prevent="handleAuth">

<input v-model="formData.username" role="username" />

<input v-model="formData.password" role="password" />

<button>Click here to sign in</button>

</form>

<span v-if="error">{{ error }}</span>

</template>

<script>

import axios from 'axios'

export default {

data() {

return {

username: '',

password: '',

user: undefined,

error: ''

}

},

methods: {

async handleAuth() {

try {

const response = await axios.post('/login')

this.user = response.data

} catch (e) {

this.error = e.response.data.error

}

}

}

}

</script>A simple login form component, It makes a request using axios.

This example uses the axios HTTP library, but the same ideas apply if you are using fetch.

We don’t actually want to make a request to a real server when testing this component - unit tests should run in isolation. One option here is to mock the axios module with jest.mock.

We probably want to test:

- is the correct endpoint used?

- is the correct payload included?

- does the DOM update accordingly based on the response?

A test where the user successfully authenticates might look like this:

import { render, fireEvent, screen } from '@testing-library/vue'

import App from './app.vue'

let mockPost = jest.fn()

jest.mock('axios', () => ({

post: (url, data) => {

mockPost(url, data)

return Promise.resolve({

data: { name: 'Lachlan' }

})

}

}))

describe('login', () => {

it('successfully authenticates', async () => {

render(App)

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('username'), 'Lachlan')

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('password'), 'secret-password')

await fireEvent.click(screen.getByText('Click here to sign in'))

expect(mockPost).toHaveBeenCalledWith('/login', {

username: 'Lachlan',

password: 'secret-password'

})

await screen.findByText('Hello, Lachlan')

})

})Using a mock implementation of axios to test the login workflow.

Testing a failed request is straight forward as well - you would just throw an error in the mock implementation.

If you are working on anything other than a trivial application, you probably don’t want to store the response in component local state. The most common way to scale a Vue app has traditionally been Vuex. More often than not, you end up with a Vuex store that looks like this:

import axios from 'axios'

export const store = {

state() {

return {

user: undefined

}

},

mutations: {

updateUser(state, user) {

state.user = user

}

},

actions: {

login: async ({ commit }, { username, password }) => {

const response = await axios.post('/login', { username, password })

commit('updateUser', response.data)

}

}

}A simple Vuex store.

There are many strategies for error handling in this set up. You can have a local try/catch in the component. Other developers store the error state in the Vuex state, as well.

Either way, the <login> component using a Vuex store would look something like this:

<template>

<!-- no change -->

</template>

<script>

import axios from 'axios'

export default {

data() {

return {

username: '',

password: '',

error: ''

}

},

computed: {

user() {

return this.$store.state.user

}

},

methods: {

async handleAuth() {

try {

await this.$store.dispatch('login', {

username: this.username,

password: this.password

})

} catch (e) {

this.error = e.response.data.error

}

}

}

}

</script>Using Vuex in the login component.

You now need a Vuex store in your test, too. You have a few options. The two most common are:

- use a real Vuex store - continue mocking axios

- use a mock Vuex store

The first option would look something like this:

import { store } from './store.js'

describe('login', () => {

it('successfully authenticates', async () => {

// add

render(App, { store })

})

}): Updating the test to use Vuex.

I like this option. The only change we made to the test is passing a store. The actual user facing behavior has not changed, so the test should not need significant changes either - in fact, the actual test code is the same (entering the username and password and submitting the form). It also shows we are not testing implementation details - we were able to make a significant refactor without changing the test (except for providing the Vuex store - we added a dependency, so this is expected).

To further illustrate this is a good test, I am going to make another refactor and convert the component to use the composition API. Everything should still pass:

<template>

<!-- no changes -->

</template>

<script>

import { reactive, ref, computed } from 'vue'

import { useStore } from 'vuex'

export default {

setup () {

const store = useStore()

const formData = reactive({

username: '',

password: '',

})

const error = ref('')

const user = computed(() => store.state.user)

const handleAuth = async () => {

try {

await store.dispatch('login', {

username: formData.username,

password: formData.password

})

} catch (e) {

error.value = e.response.data.error

}

}

return {

user,

formData,

error,

handleAuth

}

}

}

</script>Converting the component to use the Component API.

Everything still passes - another indication we are testing the behavior of the component, as opposed to the implementation details.

I’ve used the real store + axios mock strategy for quite a long time in both Vue and React apps and had a good experience. The only downside is you need to mock axios a lot - you often end up with a lot of copy-pasting between tests. You can make some utilities methods to avoid this, but it’s still a little boilerplate heavy.

As your application gets larger and larger, though, using a real store can become complex. Some developers opt to mock the entire store in this scenario. It leads to less boilerplate, for sure, especially if you are using Vue Test Utils, which has a mocks mounting option designed for mocking values on this, for example this.$store. Testing Library does not support this - intentionally - which is a decision I agree with. We can replicate Vue Test Utils’ mocks feature with jest.mock to illustrate why I do not recommend mocking Vuex (or whatever store implementation you are using):

let mockDispatch = jest.fn()

jest.mock('vuex', () => ({

useStore: () => ({

dispatch: mockDispatch,

state: {

user: { name: 'Lachlan' }

}

})

}))

describe('login', () => {

it('successfully authenticates', async () => {

render(App)

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('username'), 'Lachlan')

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('password'), 'secret-password')

await fireEvent.click(screen.getByText('Click here to sign in'))

expect(mockDispatch).toHaveBeenCalledWith('login', {

username: 'Lachlan',

password: 'secret-password'

})

await screen.findByText('Hello, Lachlan')

})

})Mocking Vuex.

Since we are mocking the Vuex store now, we have bypassed axios entirely. This style of test is tempting at first. There is less code to write. It’s very easy to write. You can also directly set the state however you like - in the snippet above, dispatch doesn’t actually update the state.

Again, the actual test code didn’t change much - we are no longer passing a store to render (since we are not even using a store, we mocked it out entirely). We don’t have mockPost any more - instead we have mockDispatch. The assertion against mockDispatch became an assertion that a login action was dispatched with the correct payload, as opposed to a HTTP call to the correct endpoint.

There is a big problem. Even if you delete the login action from the store, the test will continue to pass. This is scary! The tests are all green, which should give you confidence everything is working correctly. In reality, your entire application is completely broken.

This is not the case with the test using a real Vuex store - breaking the store correctly breaks the tests. There is only one thing worse than a code-base with no tests - a code-base with bad tests. At least if you have not tests, you have no confidence, which generally means you spend more time testing by hand. Tests that give false confidence are actually worse - they lure you into a false sense of security. Everything seems okay, when really it is not.

Mock Less - mock the lowest dependency in the chain

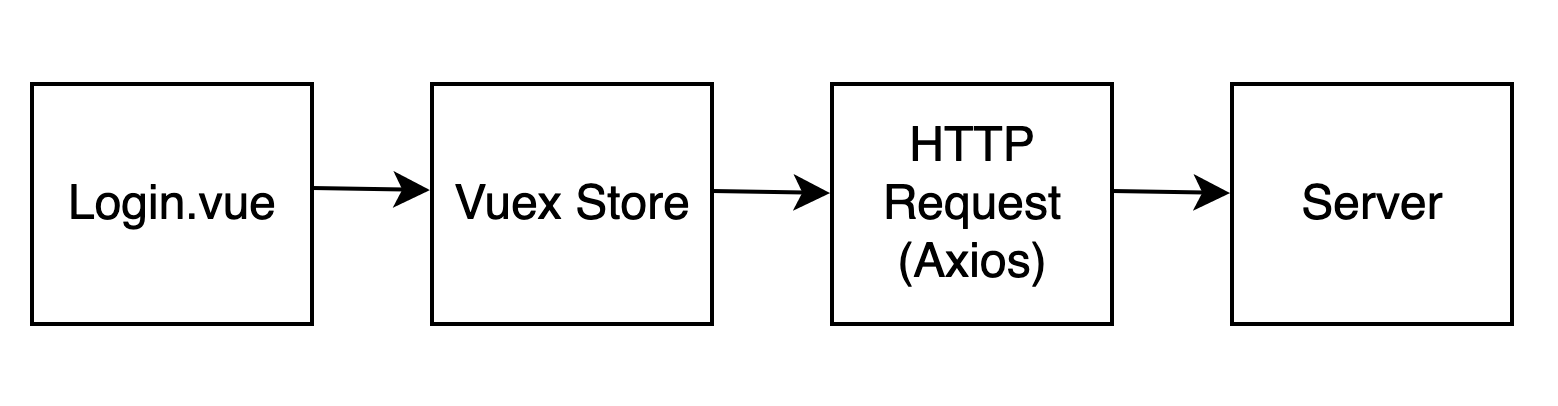

The problem with the above example is we are mocking too far up the chain. Good tests are as production like as possible. This is the best way to have confidence in your test suite. This diagram shows the dependency chain in the <login> component:

Authentication dependency chain

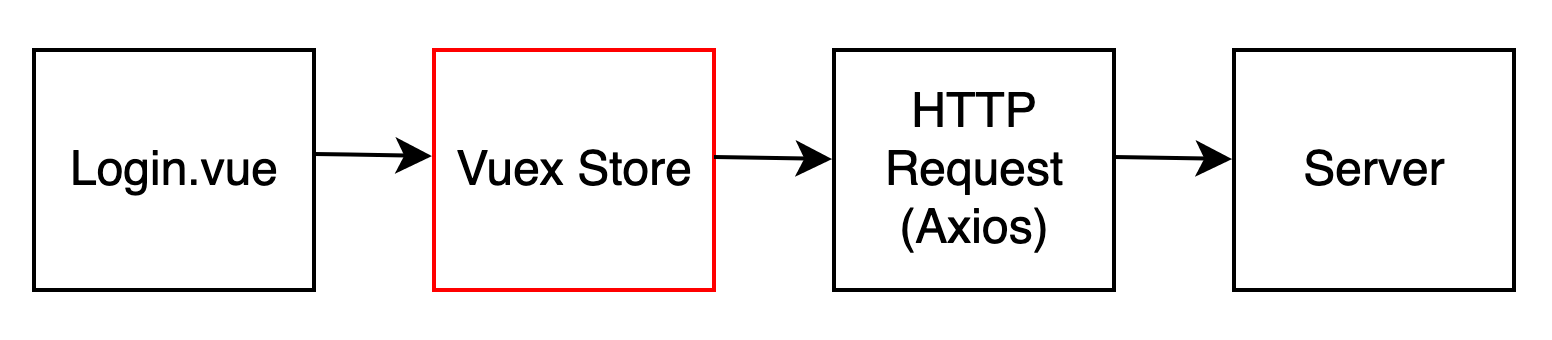

The previous test, where we mocked Vuex, mocks the dependency chain here:

Mocking Vuex

This means if anything breaks in Vuex, the HTTP call, or the server, our test will not fail.

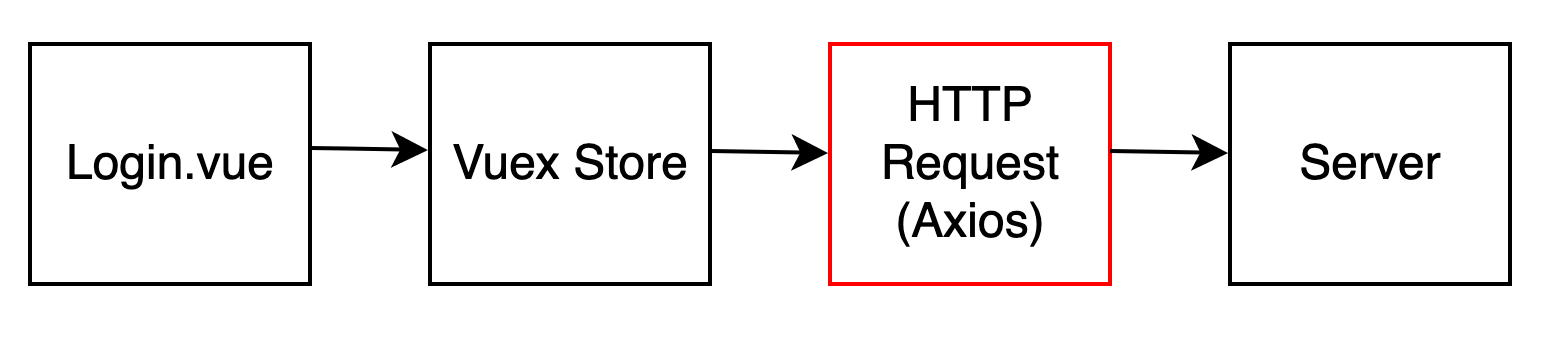

The axios test is slightly better - it mocks one layer lower:

Mocking Axios

This is better. If something breaks in either the <login> or Vuex, the test will fail.

Wouldn’t it be great to avoid mocking axios, too? This way, we could not need to do:

let mockPost = jest.fn()

jest.mock('axios', () => ({

post: (url, data) => {

mockPost(url, data)

return Promise.resolve({

data: { name: 'Lachlan' }

})

}

}))Boilerplate code to mock axios.

… in every test. And we’d have more confidence, further down the dependency chain.

Mock Service Worker

A new library has come into the scene relatively recently - Mock Service Worker, or msw for short. This does exactly what is discussed above - it operates one level lower than axios, mocking the actual network request! How msw works will not be explained here, but you can learn more on the website: https://mswjs.io/. One of the cool features is that you can use it both for tests in a Node.js environment and in a browser for local development.

Let’s try it out. Basic usage is like this:

import { rest } from 'msw'

import { setupServer } from 'msw/node'

const server = setupServer(

rest.post('/login', (req, res, ctx) => {

return res(

ctx.json({

name: 'Lachlan'

})

)

})

)A basic server with msw.

The nice thing is we are not mocking axios anymore. You could change you application to use fetch instead - and you wouldn’t need to change you tests at all, because we are now mocking at a layer lower than before.

A full test using msw looks like this:

import { render, fireEvent, screen } from '@testing-library/vue'

import { rest } from 'msw'

import { setupServer } from 'msw/node'

import App from './app.vue'

import { store } from './store.js'

const server = setupServer(

rest.post('/login', (req, res, ctx) => {

return res(

ctx.json({

name: 'Lachlan'

})

)

})

)

describe('login', () => {

beforeAll(() => server.listen())

afterAll(() => server.close())

it('successfully authenticates', async () => {

render(App, { store })

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('username'), 'Lachlan')

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('password'), 'secret-password')

await fireEvent.click(screen.getByText('Click here to sign in'))

await screen.findByText('Hello, Lachlan')

})

})Using msw instead of mocking axios.

You can have even less boilerplate by setting up the server in another file and importing it automatically, as suggested in the documentation: https://mswjs.io/docs/getting-started/integrate/node. Then you won’t need to copy this code into all your tests - you just test as if you are in production with a real server that responds how you expect it to.

One thing we are not doing in this test that we were doing previously is asserting the expected payload is sent to the server. If you want to do that, you can just keep track of the posted data with an array, for example:

const postedData = []

const server = setupServer(

rest.post('/login', (req, res, ctx) => {

postedData.push(req.body)

return res(

ctx.json({

name: 'Lachlan'

})

)

})

)Keeping track of posted data.

Now you can just assert that postedData[0] contains the expected payload. You could reset it in the beforeEach hook, if testing the body of the post request is something that is valuable to you.

msw can do a lot of other things, like respond with specific HTTP codes, so you can easily simulated a failed request, too. This is where msw really shines compared to the using jest.mock to mock axios. Let’s add another test for this exact case:

describe('login', () => {

beforeAll(() => server.listen())

afterAll(() => server.close())

it('successfully authenticates', async () => {

// ...

})

it('handles incorrect credentials', async () => {

const error = 'Error: please check the details and try again'

server.use(

rest.post('/login', (req, res, ctx) => {

return res(

ctx.status(403),

ctx.json({ error })

)

})

)

render(App, { store })

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('username'), 'Lachlan')

await fireEvent.update(

screen.getByRole('password'), 'secret-password')

await fireEvent.click(screen.getByText('Click here to sign in'))

await screen.findByText(error)

})

})A test for a failed request.

It’s easy to extend the mock server on a test by test basis. Writing these two tests using jest.mock to mock axios would be very messy!

Another very cool feature about msw is you can use it in a browser during development. It isn’t showcased here, but a good exercise would be to try it out and experiment. Can you use the same endpoint handlers for both tests and development?

Conclusion

This chapter introduces various strategies for testing HTTP requests in your components. We saw the advantage of mocking axios and using a real Vuex store, as opposed to mocking the Vuex store. We then moved one layer lower, mocking the actual server with msw. This can be generalized - the lower the mock in the dependency chain, the more confidence you can be in your test suite.

Tests msw is not enough - you still need to test your application against a real server to verify everything is working as expected. Tests like the ones described in this chapter are still very useful - they run fast and are very easy to write. I tend to use testing-library and msw as a development tool - it’s definitely faster than opening a browser and refreshing the page every time you make a change to your code.

Exercises

- Trying using

mswin a browser. You can use the same mock endpoint handlers for both your tests and development. - Explore

mswmore and see what other interesting features it offers.

Like my content? Sign up to get occasional emails about new blog posts and other content.

Unsubscribe anytime here.